Is it a bird? A plane? Neither, in fact; it’s the Hyperloop, the soon-to-be-released tube-based transportation system and newest brainchild of Elon Musk, founder of PayPal, Tesla, and SpaceX.

Heralded as the “fifth mode of transportation” – the other four being the train, plane, automobile, and boat – the Hyperloop is expected to traverse the approximately 350 miles between San Fransisco and Los Angeles in 30 minutes, which averages to a speed of 700 miles per hour, just shy of the speed of sound.

Can this be done? After spurring disruptive innovation in other industries, has Mr. Musk finally gone Hyperloopy? Or, like Ford with the popular automobile and the Wright brothers with the airplane, will this herald the new method of transportation that will forever change the rhythms of our lives?

The Hyperloop is just one example of a larger trend towards the next generation of transportation, a shift that will indelibly change our lives.

In this post, I would like to discuss 3 areas of massive change :

- the Hyperloop

- personal space flight

- innovation for automobiles

The Hyperloop

Explaining his newest project, Musk described the Hyperloop as a “cross between a Concorde and a railgun and an air hockey table,” and propels 6-foot pods through a tube.

“What you want,” said Musk, the inspiration for Iron Man’s Tony Stark, “is something that never crashes, that’s at least twice as fast as a plane, that’s solar powered and that leaves right when you arrive, so there is no waiting for a specific departure time.” In addition, it “can never crash, is immune to weather, it goes 3 or 4 times faster than the bullet train.”

Ambitious, for sure; but is it possible to travel so quickly using so little power?

The Hyperloop’s alpha plans will be released open-source in mid-August, according to Musk’s Twitter feed, and their feasibility has since been subject to intense speculation over the internet. Naysayers – to whom Musk has a penchant of saying “nay” to in turn – claim that that magnitude of speed is impossible; the Japan maglev train (short for magnetic levitation, a train powered by magnets) averages 300 mph, and more speed is impossible because of drag.

The Hyperloop’s is, in other words, a ludicrous speed.

However, other arguments claim that the Hyperloop isn’t a pipe dream. The “closest guess so far,” according to Musk, is an attempt by self-described “tinker” John Gardi, whose loop diagram looks very close to feasible. Another option is resuscitating pneumatic tubes as a mode of transportation. Pneumatic tubes are used by banks for drive-through services, and used to be utilized to send messages through large offices before the days of email.

A short history of pneumatic transportation

By using compressed air or partial vacuum, pneumatic systems propel cylindrical containers through a network of tubes, a similar function to what Musk wants to do. In fact, the history of the pneumatic tube makes this option even more appealing. After some successes in England the 1860s, an implementation of the pneumatic method of transport was attempted in London and New York, but was later stopped by financial constraints and political electioneering.

A revival of pneumatic transport was attempted nearly a century later in the 1960s, but these plans were again trashed. So, if pneumatics is indeed the nature of the Hyperloop, Musk will be implementing something that is at once very new, but at the same time is the next installment in a long line of scientists finding the practical applications of compressed air. Plus ça change.

The challenges ahead

Similarly, political opposition may be a potential roadblock for the Hyperloop as well. Musk makes no secret that he hopes to derail California’s government-funded high-speed train project by offering a transportation option along an identical route at six times the speed yet at less than one-tenth of the cost. If his venture is not careful, it, like its pneumatic predecessors, might crash on the rocks of political strife. This highlights another theme in transportation innovation, that the government has the equal potential to either help or hinder, and cannot help but play a critical role.

One assumption, however, that no critic has yet pointed out is that for the Hyperloop to work, there must be enough humans living on earth to create sufficient demand for financially feasibility.

Sound obvious?

Not to some people –including Musk himself – who are trying to boldly bring humans en masse beyond the boundaries of the final frontier: space.

Personal Space Travel – The Final Frontier, Redux

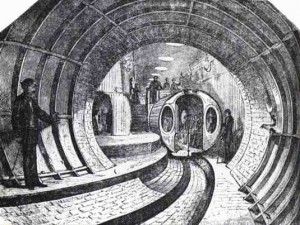

July 20, 1969: man first walked on the moon. It was, as Randy Pausch wrote, as if people were given permission to dream big dreams. And this legacy of the Apollo missions continues until today, as many people’s dreams of space flight are closer to becoming a reality…for the right price.

Commercializing space flight

“Commerical” space flight (more on what that exactly means later) as an alternative to government-dominated space launch services began in earnest in the 2000s. Previously, private interests began funding limited development programs, but what really got the ball rolling was the US government’s sponsorship of a series of programs to incentivize and encourage private companies to begin offering both cargo, and later, crew space transportation services.

In 2006, NASA decided that whereas it would still develop equipment to explore the deeper parts of space outside of Earth’s orbit, it would outsource the transportation of cargo to the International Space Station to private companies. This, it should be noted, marked a radical shift in perspective on non-governmental space travel from their reaction to millionaire Dennis Tito’s self-funded and non-governmental trip into space in 2001.

There are, broadly speaking, 2 parts to space travel:

- the space transport itself (what the shuttle was)

- the rocket to launch it to space

The private companies that meet a series of milestones relating to the creation of these two parts are given substantial funding and advice from NASA.

SpaceX and Elon Musk (again) take on commercial space flight

Now, what started as an experiment for cargo delivery has become NASA’s method for transporting people to space. This production by the private sector leads to some really interesting developments for personal space flight. Space flight is defined as flight beyond the Kármán line, the nominal edge of space, 100 km (62 mi) above the Earth’s surface.

Blue Origin’s approach

And it is the first time in history that flight beyond this boundary is being conducted and paid for by anything other than a government agency. Unlike its role in hindering compressed-air-travel (the Hyperloop and its predecessors) and the automobile (as we’ll see below), the government has critically helped the development of personal space-flight. In fact, without the government’s critical intervention, it is very likely that personal space flight would have been feasible in the foreseeable future.

But that’s not true thanks to NASA’s Commercial Crew Development program, a multi-year, multi-stage competition that provides advice and funding for private-sector companies that develop technologies for human spaceflight. The benefit to NASA is that the winner will be chosen to deliver crew to the ISS, at a much lower expected cost and with greater efficiency than NASA could do so unaided. The prospective benefit to the rest of us is that the winner will also be able to launch other crew, including civilians, into space, with NASA subsidizing its R&D and ensuring its safety precautions through its competition.

In the area of crew launch, in addition to Musk’s SpaceX, a super-secretive company called Blue Origin, funded by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is also shooting for the stars. Staying true to its motto, Gradatim Ferociter (Latin for “Step-by-Step, Ferociously), Blue Origin is making incremental progress to lower the cost and increase the safety of personal orbital flight. (Much of the information we now know about Blue Origin was found in this NASA Slideshow.) This idea, that slow and steady will win the race, is especially apt for the space race, which is more akin to a marathon than a sprint.

The Kármán line is not only an interesting factoid, but is also the border between “orbital” and “suborbital” flight. Flying beyond this line is a big technological hurdle, making suborbital flight much easier to achieve and therefore more likely to be commercially available quicker (not to mention relatively cheaper). Suborbital flight is nothing to sneeze at, though; one will be in space for a few minutes, and, though not actually orbiting the earth, still able to see the Earth’s curvature and be in zero gravity.

Billionaire Richard Branson and Virgin compete for space travel

Richard Branson’s Virgin Group created a company, Virgin Galactic, to take anyone with the requisite funds (approximately $200,000) on such suborbital flights using SpaceShipTwo, and hundreds of people have signed up even though flights are scheduled for years in the future.

However, in the long run, space flight will likely follow the same path as commercialized air flight. Airplanes, too, at their first inception were available only to the wealthy. In the infancy of the airplane industry in the 1930s, the cost of a round-trip airplane ride was $260, half the price of a new car at that time.However, over time, prices dropped as the as the technology become easier to produce. Today, airplane travel is accessible to a wider spectrum of the socioeconomic ladder. Space flight might also follow this trend.

Yes, it’s frustratingly tantalizing that even when space flight becomes available for purchase, I’ll be excluded from space travel. However, I would wager that it will not be long before we get a discount space carrier that will open up space travel to many more people (something that, in fact, Blue Origin aspires to do). So, no, in the long-run, space won’t become an extra-terrestrial Hamptons.

Drilling down on commercialization and the role of the private sector

“Commercialized” space flight, then, has substantial momentum. However, what does it mean to be “commercialized”? I had originally assumed that the private sector would be shouldering most of the risk and cost of these flights; however, it seems that the government is paying 80-90 percent of the costs for the development of these “commercial” systems. NASA spent about $800 million on the commercial cargo program for system development, and plans to spend $4.8 billion through 2017 supporting commercial crew systems development. How much the companies themselves are investing, though, is proprietary information.

So what exactly is the private sector doing?

Second, space travel is not only by the private sector but for the private sector, meaning personal space flight. “Commercial,” then, means “commercialized.” Anyone who dreamed of being an astronaut as a child may finally have her chance of achieving that dream…for the right price, a price that will hopefully decrease in my lifetime (alternatively, I wouldn’t mind becoming rich enough to afford the current prices – that would work, too).

And though it sounds hokey, the theme of dreams shouldn’t necessarily be downplayed. Humans, for as long as we’ve been around, have been looking heavenward, trying, yet never succeeding, to touch the cosmos. But now we might have that chance, many if not all of us. Space still casts its spell upon star-gazers, throughout the world.

Israel’s SpaceIL

A group of young Israeli scientists have founded SpaceIL, with the goal of making Israel the third nation on the moon. SpaceIL is the only not-for-profit entry in the Google Lunar X Prize, a competition that awards $20 million for the first privately funded venture to land on the moon.

And the success of the all-American SpaceX is an extra boon to America when it needs it most. At a time of a shaky economic recovery and a widespread feeling of pessimism about the future, the innovation, especially by the private sector, to once again reach for the stars and, amazingly, to reach them might be enough to re-inspire the hope from one man’s small step in the summer of 1969.

Re-Inventing the Automobile

Do you find the Hyperloop and space travel too futuristic for your taste? Or, are you wondering what you can do about it now, and aren’t interested in waiting a few years, at the very least, to enjoy the benefits of transportation innovation?

Well, then, let’s talk about some more current innovations centering around the oldest form of mass transportation: the automobile.

Though they don’t necessarily have the “cool”-factor of space travel or the Hyperloop, a few new car-focused apps are perhaps no less innovative, though their change is wrought by evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, measures. They improve existing, daily forms of travel, and will most likely have the biggest impact of all the innovations discussed here on the on the way we travel in the short- to medium-term.

Changing the way we drive…with apps

Waze, the Israeli startup which made headlines after being acquired by Google for over $1 billion, is a free GPS app that aims to “outsmart traffic, together.” Based on its user-generated knowledge of traffic, Waze calculates the quickest route from Point A to Point B. Waze notifies drivers construction detours, accidents, and other commuting frustrations, and such helpful data are likely to increase after the Google acquisition.

A similar family is that of taxi applications, including Uber, GetTaxi, and Hailo. Avoiding the need to flail one’s arms or wait despondently on a street corner, these apps allow users to order cabs on their phones. Like other innovations mentioned above, regulatory agencies have been up in arms about these apps, and though several legal issues have been worked out on a case-by-case basis, it has yet to be seen whether all involved parties can agree on how to make this work. Hopefully governments will err on the side of helping and not of hindering.

Electric cars are on their way

Electric cars, though, still seem to be the next big goal for automobile innovators, to protect the environment from the harmful burning of fossil fuels as well as to free drivers from the tyranny of volatile oil prices. In fact, electric cars enjoyed modest success around the turn of the 20th century before the internal combustion engine became efficient and safe enough for mass use, and, despite a brief interest with the rise of oil prices in the 1970s, electric-powered vehicles have remained an elusive goal for mass consumption. The central problem of cars not running on gasoline is keeping the batteries charged so that the car can, well, function. The leader in this industry is Elon Musk’s Tesla Motors, which has reportedly neared profitability, and aims to create an affordable family car in the near future.

For electric car enthusiasts, though, there has been one serious setback: the disappointing failure of the much-anticipated Israeli startup Better Place, a company that embodied the innovation, drive, and sheer chutzpah of the Start-Up Nation, after years of excitement and over $800 million of venture funding. Israelis, though, are still optimistic about electric cars, and believe that their small country is an ideal market for electric cars, as some companies attempt to salvage Better Place’s national electric infrastructure while others attempt to import electric vehicles. Though Better Place is gone, Israeli chutzpah remains.

Self-driving cars and Google

If so, incremental stages of automation will make their way into consumer automobiles before total driving automation is accepted. Even today’s car models include such automated features as: adaptive cruise control, which adjusts for other cars ahead, and automated parallel-parking, even in the relatively affordable Ford Focus. Mobileye is an Israeli company that provides automated detection systems to help drivers be safer on the roads by preventing collisions.

Transportation technology: Changing the way we move in fits and starts

The incremental adoption of automated navigation technology, then, perhaps represents other innovations in transportation. As Bezos’ Blue Origin exemplifies, Gradatim Ferociter; “Step-by-Step, Ferociously.” The Hyperloop will not be built overnight. Space travel, even when developed, might be available only for a select few. Even with the relatively developed automobiles, there will be discouraging failures, like Better Place.

But more important than how victories are celebrated is how losses are dealt with. The Israelis offer the perfect model, as only six weeks after Better Place’s bankruptcy, other Israeli companies were forging ahead with the electric car process. They licked their wounds, picked up, and carried on.

The road ahead is not linear, whichever form of transportation you prefer. But there is only one thing that is certain: the future of transportation will certainly not be boring.

[xyz-ihs snippet=”ShlomoKlapper”]