There was a meteoric rise in blockchain popularity in 2017. Everyone was in on it. The barber replaced chit chat about hot new stocks with advice about cryptocurrency portfolios. Cab drivers were fluent in ICOs. It was new, it was exciting, it was like investing in the internet in the 1990s.

Many point to ICOs, or initial coin offerings, as a major catalyst for the cryptocurrency craze that took hold from 2017-2018. A simple way to understand an ICO is to think of it as a token at an arcade like Chuck E. Cheese’s. But imagine being able to buy tokens before the arcade ever opens. Tokens can only be used for this specific arcade, have a fixed supply and are not tied to any currency. Once the arcade has its grand opening, prices move up or down based on demand. Naturally, buyers holding onto “pre-launch arcade tokens” hope for a significant uptick in demand, driving prices higher. On the one hand, this demand would result in more games being played, blockchain companies sell digital “tokens” that can be used for data storage, computing power, or even casinos. The “tokens” are new cryptocurrencies and the sale before the arcade launches is the ICO. Blockchain takes care of the limited supply, easy trading and a few other more technical aspects.

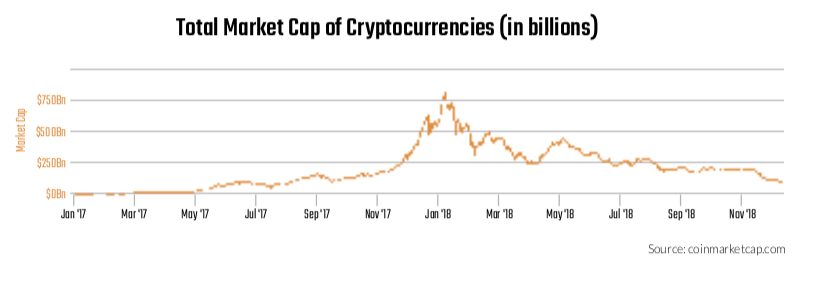

Midway through 2017, the blockchain craze was at full throttle. Ethereum—an open smart contract platform based on blockchain technology—grew a whopping 2800% from January to May. Ethereum’s exponential growth drove companies to build on top of the platform, creating new uses that piggybacked on the underlying technology. How did many of these companies raise funding? Through ICOs. It turned into a feeding frenzy of investors looking to gobble up any semi-legitimate ICO investment with the hope of finding the next Ethereum.

Since companies sold a fixed number of tokens to the general public on a first-come-first- serve basis, they were raising tens of millions of dollars in minutes, even seconds. For example, Basic Attention Token, a highly sought-after digital advertising project, raised $35 million in 30 seconds. Investors grew upset because they were getting locked out of ICOs, so companies took the next logical step: they raised larger ICOs.

It soon became common to see companies raise $100+ million ICOs. Israeli companies Bancor and Sirin Labs raised over $150 million each. Decentralized cloud storage company Filecoin raised over $250 million. Encrypted messaging service Telegram raised $1.7 Billion. Smart contract platform EOS raised over $4 billion in an ICO.

Now comes the catch. It is important to note that investors in the above ICOs did not receive equity in the companies. They received something that could be used in the future, whenever the company eventually built a product.

After raising $230 million in an ICO, Kathlene Breitman, co-founder of blockchain platform Tezos, told Reuters that “participating in the Tezos fundraiser was like contributing to a public television station and receiving a ‘tote bag’ in return.” Not surprisingly, Tezos was hit with multiple lawsuits in the months after the ICO. In the second half of 2017 and the first half of 2018, ICOs raised a whopping $11 billion in funding, but the euphoria would soon fade.

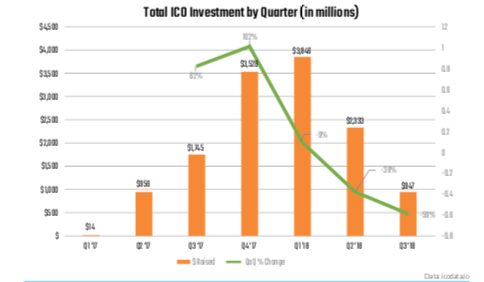

In mid-2018 the cryptocurrency market plummeted over 75% in only a few short months. In turn, ICO investment dried up. After experiencing up to 102% QoQ growth, 2018 saw investments shrink by up to 59% QoQ. The change between October 2017 and 2018 is even more radical. October 2017 saw $885 million in ICO investment compared to $54 million in October 2018, a YoY drop of over 93%.

After looking at the incredible rise and fall of ICO investment, the obvious question is what happened? Why did the ICO investment well dry up so fast? Most experts point to two main factors, both of which are dirty words in finance: scams and regulators. A study by the Statis Group found that 80% of ICOs conducted in 2017 were scams. As news spread about these rampant scams, interest dropped and money stop flowing.

Regulators in multiple countries also began to chime in on the ICO market. Companies raising money began to call tokens sold via an ICO “utility tokens.” This term was coined for two reasons. It indicated that the tokens were in fact going to be used for a service, giving them utility and thus circumventing the word “security.” If the tokens sold were in fact securities, then local regulators would need to get involved, creating new requirements for an ICO and restricting who could potentially invest.

The problem is that 99% of the time, companies had not built any type of product yet. Regulators saw that people were speculating on the potential increase in price as opposed to looking to buy a service in advance. ICOs became securities events, and companies either had to change their plan or risk being shut down by local regulators. While these two reasons definitely impacted the decline in ICOs, there are two underlying factors that do not receive enough attention but may have had a greater effect on ICOs dropping off.

First, the tech is not there yet. Going back to regulation, the main issue was that companies were raising ICOs but were unable to release a product for months, if not years. This lag makes sense because blockchains are not easy to create. Back before Wix or other web design products, it could take weeks, if not months, and thousands of dollars to create a website. The same is true with the current blockchain space. “Blockchain investment is like the internet in the 90s, but blockchain technology is like the internet in the 70s,” said Anthony Macey, Blockchain/DLT Lead at Barclays, at an event at Barclays Rise in Tel Aviv.

Second, ICOs were already dead by the middle of 2017. There was of course plenty of money flowing into ICOs. There is no question about that. But the initial vision of what an ICO should be was already gone. ICOs were supposed to help communities support projects in which they believed, not something used to make a buck. Most early purchasers of cryptocurrencies saw tokens as creating a new way of life, not another asset within a portfolio.

Take the Basic Attention Token ICO mentioned above. One buyer purchased nearly 13.5% of the ICO for $4.7 million, which seems more like a Venture Capital or Private Equity firm taking a position within a company. The proof is in who is signing the biggest checks: funds. Three of the top funds in the blockchain space are Digital Currencies Group, Pantera Capital and PolyChain Capital. At first glance, those names may seem new to the average investor, but here is a list of those funds’ LPs: Benchmark Capital, Fortress Investment Group, Andreessen Horowitz, MasterCard, CIBC Capital, Western Union and New York Life Ventures.

These institutions likely saw the meteoric rise of ICOs and, just like startup investments or private equities, took large positions in high-risk investment in order to capitalize on potential profits. Institutional involvement allowed startups to go through private channels, opting for either equity or “SAFTs.” These “Simple Agreement for Future Tokens” are similar to convertible notes in the startup world, except the asset converts to tokens instead of an ownership percentage. As SAFTs and equity rounds became popular, retail investors found themselves in the same boat as investing in private companies: locked out of the best deals.

Although there is much uncertainty ahead for the blockchain space, one thing is clear: ICOs as we knew them are dead.

About the Author

Josh Liggett is an investment analyst and fintech lead at OurCrowd. He also serves as a mentor at the Barclays/Techstars accelerator in Tel Aviv and advisor for BlockChain Israel.

Download OurCrowd’s full Q4 Corporate Innovation Report here.

![Reality check! Mapping the Israeli VR and AR startup landscape [Infographic]](https://blog.ourcrowd.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/VR-AR-infographic.min_.jpg)